Adapting Perspective to Chinese Taste

CASE 3

Culture and International Relations in the 18th Century

We can see that when two cultural traditions encounter each other, there will always be some kind of mutual adjustment and negotiation. This process of negotiation often gives rise to creative new forms that differ from anything known previously in either cultural tradition. We can see this process of negotiation at work in the case of perspective. Although the European Pavilions were the first demonstration of linear perspective in China, they also incorporated many elements that reflected Chinese taste, thus becoming hybrid creations. We already mentioned that they had Chinese-style roofs. In addition, mostly Chinese plants and trees were used for the landscaping, as well as animal and numerical symbolism. Most importantly, the pavilions were arranged according to Chinese ideals of garden design.

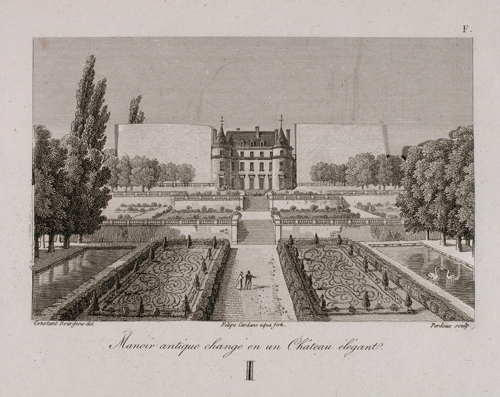

Example of an “elegant” eighteenth-century French garden with its rigid symmetry allowing for strict perspective views.

Nouveaux Jardins de la France et ses anciens chateaux, 1808.

Courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks.

A European palace of this time would have arranged the gardens behind one grand building from where the viewer could gain a single perspective. Chinese gardens were, in a sense, “pluralistic,” built to emphasize a variety of views and perspectives, often offering multiple views of the same spot!

Europeans were fascinated with this aspect of Chinese gardens, and, as the grip of aristocratic and religious authority began to weaken in Europe, people became increasingly attracted to Chinese ideals of naturalness and multiple perspectives. They noticed, for instance, that in a Chinese garden a visitor was supposed to meander through it, as if in a painting or a natural landscape. Emperor Qianlong did not abandon this aesthetic ideal, as indicated by the arrangement of the European Pavilions.

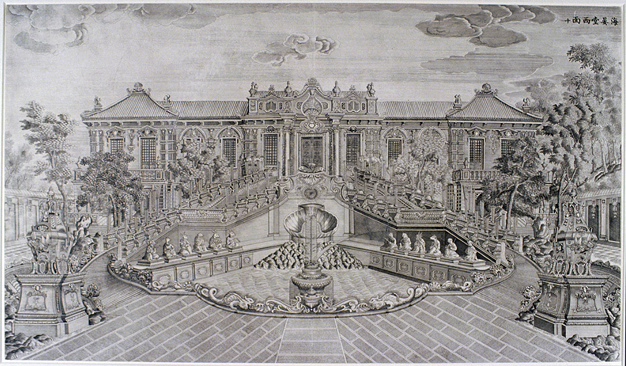

Hall of the Calm Seas.

Series of 18th-century engravings by Li Yantai

of the Yuanmingyuan Palace.

Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Also, in deference to the notion of perspective, the European Pavilions were placed in a sequence that was close to a straight line but not exactly straight so that the emperor could not quite see the entire garden from any one point. Each area was screened by gates, walls, and trees, creating an effect of surprise for the passing visitor. It was only when the emperor arrived at each pavilion that he could experience linear perspective within that particular scene. In some places, he could have broader views, such as those provided from the second floor of the Hall of the Calm Seas. But he would not have found it interesting to see everything in the garden all at once. In this way, the pretense to a universal view underlying European perspective was subverted by dividing the view into smaller scenes. In this way, the garden continued to make use of the Chinese association between “scene and feeling” (qing and jing) and the corresponding emphasis on multiple perspectives.