| Musical activities serve many social functions. These can range from expressing one’s personal emotions, to entertaining paying patrons, to playing an active role in historical, cultural, or social situations. Three famous cases from Chinese literature and history demonstrate some of the roles pipa has played in cultural and social interactions.

The first case involves Pai Juyi’s “Ballad of the Pipa,” a narrative poem that tells of the poet’s encounter with a pipa courtesan one autumn night in the year 815, a time when he had been banished from the capital and demoted to the rank of local official Jiujiang. While hosting a farewell party for a friend on the Pen river and drinking wine, he becomes depressed by the occasion and by the lack of music. When he hears pipa music coming from another boat, he moves his boat closer to the performer’s boat and has a musical and social encounter with her, in which they share their life’s frustrations.

The poem includes many celebrated phrases about pipa music. Some describe its musical features, comparing the sound of pipa to a “rush of rain” or a whispering of personal secrets. Other phrases describe standardized pipa performance techniques, each of which produced distinctive sounds and had distinct meanings. And others not only give the titles of historical musical compositions, such as “Rainbow Skirt” (“Nichang yuyiqu”) and “Sixes in Dice” (“Liuyao”), but also describe musical styles identifiable as those of the entertainment quarters in the Tang capital, Chang’an. Through these musical and cultural references, the poem conveys how indispensable an element of social life pipa music was in the Tang period. “Rainbow Skirts” and “Sixes in Dice,” it should be noted, are not just the titles of the best banquet music from the Tang court—they also give a sense of its elite patrons, who alone were able to afford such entertainments. Poetic allusions to the musical skills of courtesans suggest that the social function of entertainment music performed by women was to charm male clients. The poem also suggests that the courtesan used pipa music to vent her frustrations, which tells us something about Tang gender roles: though Tang men could freely express themselves in all kinds of public and private acts, most Tang women, with the exception of the elite or courtesans, were able to express themselves only with intimate pipa songs played privately to themselves.

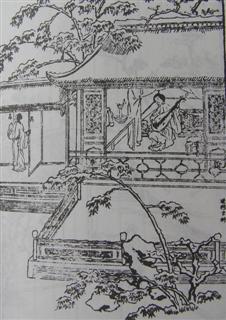

The image of a woman lamenting with pipa music constitutes a trope in Chinese romantic literature, a fact that is vividly illustrated by chapter 38 of the famous late Ming novel, Jinpingmei. Chapter 38 contains a description that is skillfully crafted into two sections. The first shows how sad, and thus erotically alluring, the female protagonist is; the second shows how musical laments cause her audience to behave in particular ways and help her to get what she wants. Jin Pingmei laments and plays a pipa. The image of a woman lamenting with pipa music constitutes a trope in Chinese romantic literature, a fact that is vividly illustrated by chapter 38 of the famous late Ming novel, Jinpingmei. Chapter 38 contains a description that is skillfully crafted into two sections. The first shows how sad, and thus erotically alluring, the female protagonist is; the second shows how musical laments cause her audience to behave in particular ways and help her to get what she wants. Jin Pingmei laments and plays a pipa.

The story describes how on a snowy night, Pan Jinlin, the female protagonist, softly plays the pipa in her boudoir, hoping that her husband, Ximen Qing, will appear in her quarters. Because she is tired, she falls asleep, only to be woken up by the sound of falling snow, and to realize that her husband has not yet come to her. Trying to force herself to stay awake so that she can welcome him should he come, she takes up the pipa and sings. She is eager to know where her husband is, so she sends her maid to find him and learns that he is in another concubine’s quarters. Upon receiving this news, Pan cries, hangs her pipa high, and proceeds to sing out her frustration. |

The chapter then describes Pan’s husband, Ximen Qing, who is frolicking and drinking with Li Pinger, another concubine. When he hears Pan’s pipa lament, he realizes that she is still awake and lonely. He sends a maid to fetch Pan, but she will not come. Then Ximing Qing, Li and the maid go over to Pan’s quarters, force their way into her room, and find her sitting on her bed with her pipa lying by her side. After several verbal exchanges, Ximing Qing drags Pan to Li’s quarters, where they play chess and drink wine. But Li, having been moved by Pan’s lament and realizing how love-sick she is, pushes Ximeng Qing to Pan’s side and lets them spend the night together. Though this description is fictional, it accurately portrays the ways pipa music could communicate desire and be a catalyst for particular emotions and social actions.

Another social function of pipa music is reported in the story of Zha Bashi, a Ming male and elite pipa virtuoso (fl. ca. 1560s). Zha of Huizhou is born to a rich family and has the means to spend his life pursuing the art of pipa playing. As a young man he travels widely, searching out pipa masters and learning from them. One of his teachers is the esteemed master Zhong Xiuzhi of Anhui Province. Years later, Zha is invited to drink and play pipa music in a courtesan’s studio. Zha accepts the invitation, but takes his own instrument along because he does not want to play pipas provided by the courtesan, which he assumes will be of inferior quality and not equal to the force of his masculine playing. The studio to which he is invited, however, belongs to the Yang family, who happen to have a long tradition of pipa playing. After some drinking of wine, Zha begins to perform, accompanied by a courtesan’s rhythmic playing of the clapper. As they play, a blind old lady who was once a musician herself, listens from an adjacent room and immediately recognizes something distinctive about Zha’s music. She quickly sends a messenger to tell the courtesan that she has not properly marked its beats. A while later, the old woman joins the music party and asks Zha from whom he has learned his music. Zha tells her that he was once a disciple of the master Zhong Xiuzhi, who turns out to be a close friend of the old lady. When they realize the musical and personal connections between them, they embrace each other and cry.

What this story underscores is that when music of distinctive styles is performed in a particular context, it can communicate messages that will prompt predictable actions and responses. Had the old lady not been a close friend of Zhong Xiuzhi’s and known his pipa music intimately, and had Zha not faithfully preserved and played the pipa music he learned from Zhong, their emotional encounter in a courtesan’s studio years later and their shared memories of the master would not have occurred.

In this story the embrace shows the particular cultural and social values that pipa music can convey. Here the music sonically communicates its participants’ social identities and status. The story shows that music is held in high esteem when it has been faithfully transmitted from established male teachers/ancestors to legitimate male disciples/descendants. But by faithfully performing Zhong’s style of pipa music, Zha does not just legitimize himself as the artistic descendent of a past master; he also elevates the status of his music, and thus his personal and social status.

Pipa projections of social identities and values still make powerful statements. To illustrate this one only needs to examine the dynamic performances of and scholarship concerning “Ambushed from Ten Sides.” What is important about this piece goes well beyond the historical question of how the piece originally sounded and how it has changed from the late Ming to the present day. For performers, the way they play the piece helps define their musical ancestry, legitimacy, and expressions. For example, pipa maestro Lin Shizheng’s art and his authority cannot be separated from his identity as the foremost representative of the Pudong School of pipa music, a tradition that can clearly be traced back to a master active at the turn of the nineteenth century. This is also why Wu Man, an international superstar among contemporary pipaists, publicly announces herself as a student of Lin Shizheng: by linking herself with a centuries-old Chinese heritage she increases the value of her art and her status as a performer.

|