HOW DID IT EVOLVE IN HISTORY

CASE 6: Pipa as a Window on Chinese Music

As it is currently known, the Chinese pipa is a hybrid of a native plucked instrument and a lute imported from Persia; the evolution of the pipa probably took place over a long stretch of time and involved a multitude of musicians, many of whom were non-Han. Stories about the origin of the pipa often claim that the hybrid pipa was first developed to provide musical consolation to a Han Chinese princess sent in 105 BCE to marry a Tartar chief. This story claims that musicians studied the features of zithers and other instruments in order to make a portable instrument that they could play while riding horses. In another popular account, one that is often repeated in dramatic texts and performed on Chinese stages, Wang Zhaojun 王 昭 君 is said to have played the pipa to lament her misfortune. 1 Wang Zhaojun was a commoner who was first recruited into the Han palace sometime between 49 B.C.E. and 33 B.C.E.; later she was married off as a princess to a Xiongnu 匈 奴 chief. It was only after the marriage had been arranged that her great talent and beauty were recognized, and her departure lamented inside the Han palace.How this Han dynasty pipa is related to the pipa-lute imported into China from Persia is not known. It is known, however, that what was imported was a quxiang pipa, a plucked lute with a pear-shape resonator, a short and bent-neck, and four frets; during performances it is held horizontally and played with a plectrum.

Historical writings from the Tang and Song dynasties copiously report the wide use of this type of pipa in the court and among commoners. The Tang History, for example, records that it was used in the renowned ten ethnic orchestras and in repertories of entertainment music performed in the Sui and Tang courts. Actual examples of quxiang pipa that have been preserved in Japan indicate the organological features of the instrument. They also show that it could be extensively and luxuriously decorated, signs that the instrument and its music had achieved a very sophisticated level of development and had been embraced by wealthy and elite patrons. To imagine how these pipa/biwa might have sounded, one can listen to traditional Japanese gagaku, which some practitioners and scholars have described as a direct descendant of the music exported from Tang China to Japan.

(Music example 6: A performance of Japanese gagaku.)

The evidence supporting this claim comes from the Dunhuang pipafu (music scores from Dunhuang, China), one of the earliest decipherable notations of Chinese music, which show direct relationships between gagaku notation for the biwa and the popular notation for ci songs of Song China.

Music example 7: Ye Xuran performs

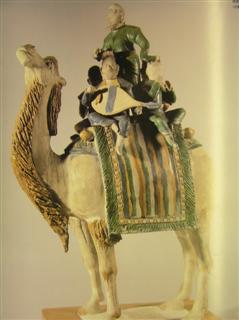

“Qingbeile.”Archeological objects, such as figurines of non-Han musicians playing the quxiang pipa while riding on camels, suggest how the instrument was imported into and popularized in China.

Illustration 10: “A Tang dynasty ceramic figure of a non-Han musician playing a quxiang pipa while riding a camel.”

Numerous depictions of pipa, including those found in the mural paintings at Dunhuang, are evidence of a quite vibrant pipa culture in the Tang and Song periods.

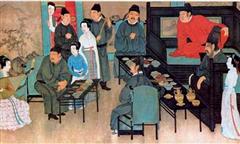

The sensuous depiction of the pipa playing angels in the Dunhuang mural paintings evokes the pleasures their performances must have given to their patrons, while the variety of musical and performance details suggest the breadth and scope of Tang pipa. This included not only court music and dances featuring pipa, but also use by Buddhist monks, who, historical sources confirm, promoted their belief by singing Buddhist chants and telling stories with pipa accompaniments.Of all the historical sources that suggest the sophistication of pipa music in Tang China, one piece of pictorial and one piece of verbal evidence are particularly noteworthy. The pictorial evidence is a painting by Gu Minzhong (910-980 CE) that is now known as “Han Xizai entertains at night” (“Han Xizai yeyantu”). The painting is a representation of musical parties in the home of the scholar-official Han Xizai (d. 970 CE). The story tells how Li Yu (937-75 CE), the ruler of the Southern Tang (937-975CE), sent the painter to investigate the private life of the scholar-official; the painter then reported what he saw in the form of the painting. In its first section, the painting expressively captures a group of seven elite males and their four female companions attentively listening while a female pipaist plays a quxiang pipa.

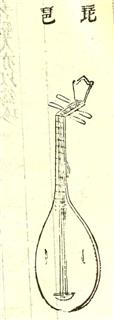

As the quxiang pipa became more widely used it was adapted to specifically Chinese musical needs and preferences. By the late Ming dynasty, a new version of pipa emerged, one that closely resembled contemporary Chinese pipa and was commonly used in many genres of Chinese song, theatre, and ensemble music. This is proved by two Ming publications. One is the renowned Sancai tuhui (Collected illustrations of the realms of heaven, earth and men 三 才 圖 會), a practical encyclopedia for living published in 1609. In it Wang Qi王 圻 illustrates a pear-shaped pipa with a long bent neck and more than ten frets.

A similar pipa appears in a 1610 edition of late Ming dramatic texts.By the late Qing dynasty, pipa solo music became established, a development reflected in the rise of a number of distinctive schools of solo pipa music. Five of these schools and their leaders have played an important role in the development of 20th-century pipa music. First among these is the Pudong School, founded by Ju Shilin (flourished 1790s to 1800s) and developed by Lin Shicheng (1922-2006). Lin transcribed and edited Ju Shilin’s traditional scores into a modern notation, and published this as Ju Shilin pipapu (Ju Shilin’s pipa notation) in 1983. Lin’s performance of pipa music is widely available on commercially produced CDs.Since the 1950s, the pipa has been altered to meet new demands, such as those created by large concert halls. A few obvious changes include the following: more frets have been added to expand the range of tones to almost four octaves; the placement of the frets has been adjusted to reflect modern pitch temperament and tuning; and silk strings have been replaced by metal strings wrapped in silk. The contemporary pipa thus projects a dynamic sound that can reach large audiences, and with the new tuning, the pipa can be used to play music in any style. As the pipa’s expressive power has attracted more and more interest, it has become a global musical instrument.Video2: Yang Wei plays a New Zealand folksong on the pipa.Video 3: Yang Wei plays the “Star Spangled Banner.”

Go to the next section to read about the Pipa’s GLOBAL CONTEXT.