WHAT IS THIS THING?

CASE 7: Homicide and the Law in 18th Century China

The document we have here is a complete case record of the crime, from the initial reports to the final imperial endorsement of the investigation and its conclusions.

In this case, the record documents the mysterious disappearance of a husband, wife and son. The brother of the husband accused several individuals of conspiring to kill his brother and make off with his wife and son. The investigation revealed that Ms. Zhou (the wife of the murdered man), her lover Yuan Ren, and several other accomplices were responsible for the brutal killing of the plaintiff’s brother. Ms. Zhou was an active instigator and willing participant in the murder of her husband, which is most shocking given the prevailing notion of ideal feminine virtue.

Thousands of cases underwent judicial review each year and at each succeeding level of review, the presiding official provided a separate report and a provisional sentence. As a result, complete case records were voluminous and repetitive, but it appears that this was considered necessary to ensure a just decision. Although this report has passed through each ascending level of judicial bureaucracy, the case record is built on the foundation of the district magistrate’s report, which was the most extensive and comprehensive. In this particular document, the reports of the county level officials comprise about three quarters of the entire document.

Title page of the Murder case of Wen Shaolong

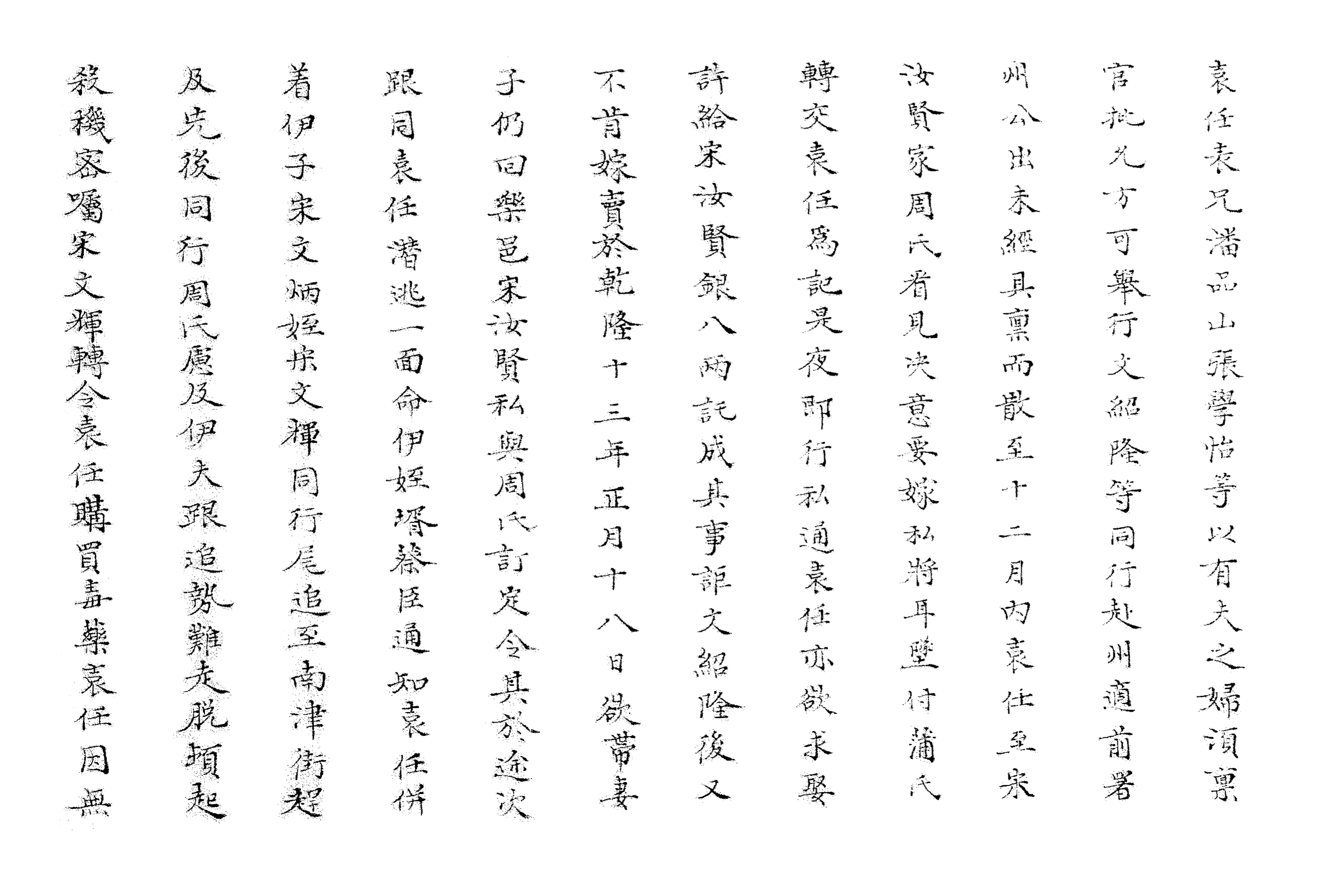

The document we’re looking at is a routine report from the Board of Criminal Sentencing (刑科題本) that has received the endorsement of the Qianlong emperor in vermillion ink. Akedun, the President of the Board of Criminal Sentencing and the highest judicial official in the Qing government, was the “author” of this report. Of course large portions of his report are quoted from the reports of the Governor General of Sichuan and the Sichuan Surveillance Commissioner, who in turn quote from the reports of the prefectural and district officials. Undoubtedly office staff from the Board of Criminal Sentencing compiled the final report, though Akedun would have been responsible for any errors in it. The vermillion characters on the first page, as shown here, ostensibly handwritten by the emperor, dramatically represent the imperial endorsement of the guilty verdict and the proposed punishments.

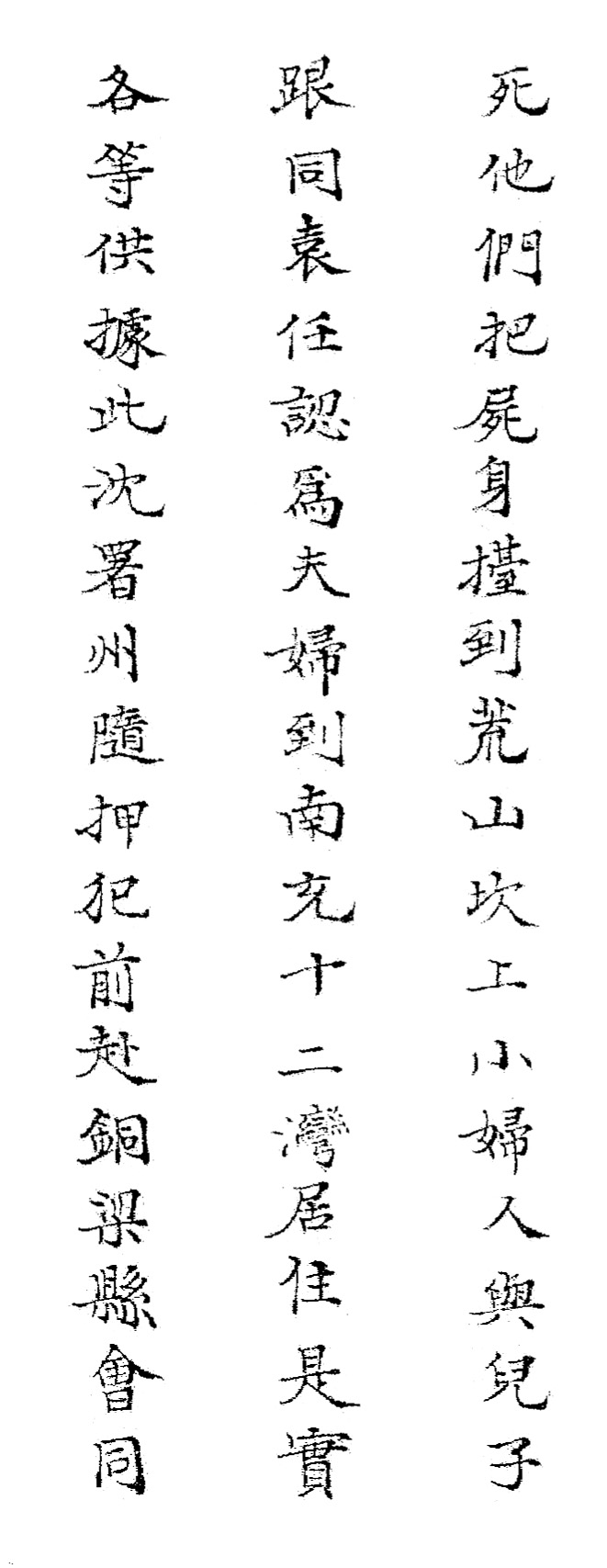

As with government reports today, the format of a routine official document was standard. On each page of a criminal report there would be twelve columns of text, and with the exception of an initial column listing the titles of the reporting official in small print, each column was filled with eighteen characters.

First page of the case record of the murder of Wen Shaolong

This uniformity was made possible by the fact that all Chinese characters are the same size, whereas a word in English could be as short as a letter or as long as ten or more. So while page length or size is often prescribed in number of inches in the U.S. and other countries with alphabetic languages, page size was usually set by the number of characters in China.

The only exception to this format was when reference was made to the emperor directly or indirectly. In those instances the column ended and the reference to the emperor began a new column elevated one space higher than normal, as seen below. This was a conventional way of showing respect. The same convention could be used in ordinary correspondence when one wished to show special reverence say, to an elder member of the family. In the case of the emperor, however, this practice was prescribed.

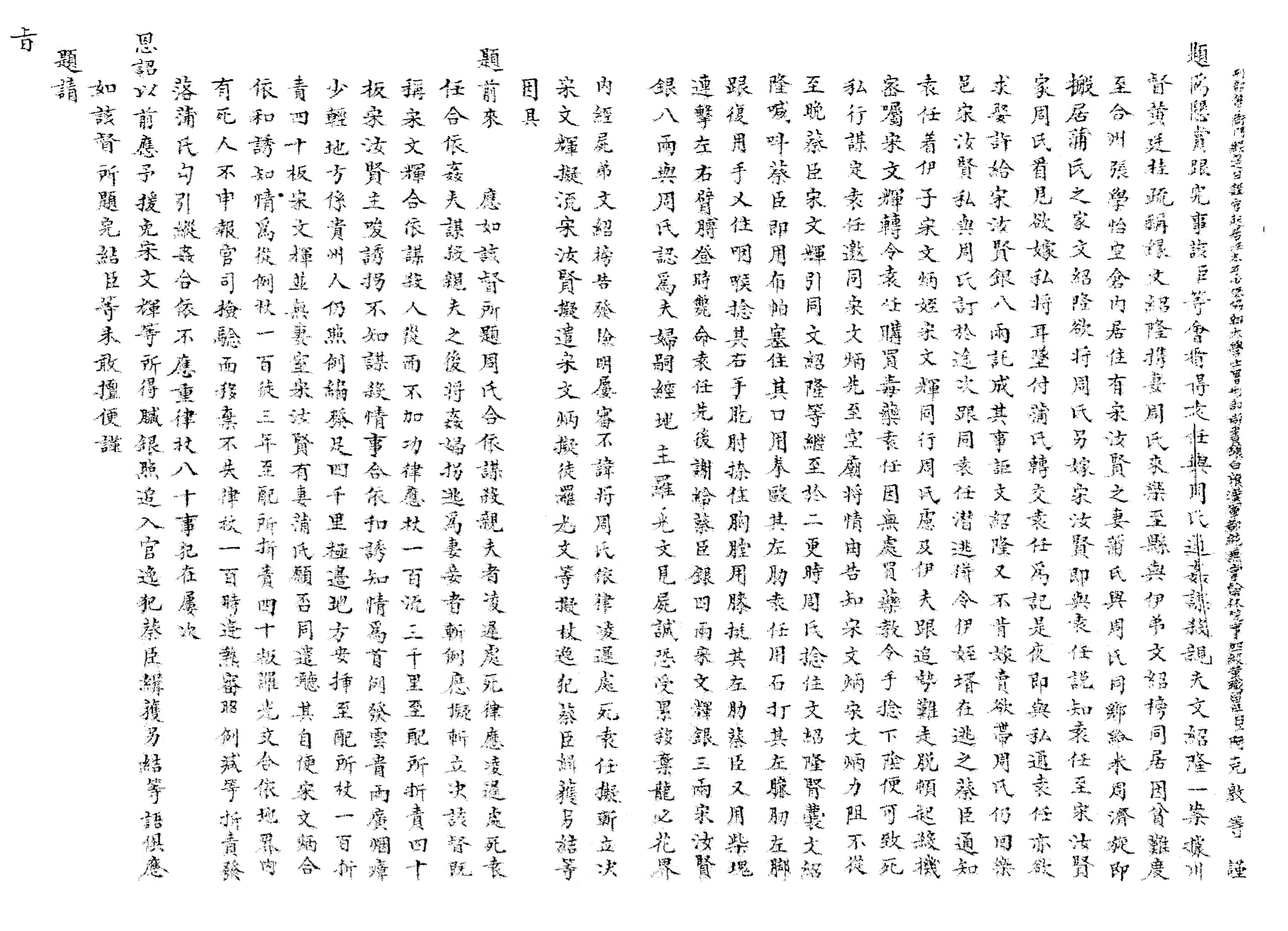

Last page of the case record of the murder of Wen Shaolong

At the end of every document was a brief synopsis of the case. This “executive summary” was written in smaller print and consisted of a barebones narrative of the case that included all the legally essential facts. Thankfully, the clerks who copied the case records printed each character with exceptional clarity.

This is not to say that they did not occasionally make errors in transcription. Indeed by eighteenth-century standards, this document is a bit sloppy. A discerning eye will find several places where additional characters were squeezed into a column.

Except under rare and extraordinary circumstances, capital cases in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) were initially tried at the district level and subsequently underwent automatic retrial and review at the prefectural, provincial and central government levels. This practice originated during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) because, as one Han dynasty statesman put it, “People’s lives were considered precious.” Indeed, after passing the various higher courts, the verdict would have to be endorsed by the emperor himself before anyone could be executed. This process ensured that the facts of every capital case would be reviewed repeatedly by multiple individuals. Presumably this reduced the likelihood of irresponsible decisions or the loss of innocent life.

Sample of calligraphic style in the case record of the murder of Wen Shaolong