Ink Plum Blossom: THE GENRE

Ink Plum Blossom: The mirror image of a scholar in the Song Dynasty

by Gerui Wang (University of Michigan, 2014)

Plum blossom and recluse

Since the early Northern Song period (960–1127), for intellectuals in the Song Dynasty, the plum blossom represented values of a scholar-recluse. Hence the imagery of plum blossom in Song Dynasty art and literature created by scholars often associated with scholar-recluse ideals. A scholar-recluse embraced and practiced integrity and intellectual independence. Tired of officialdom and disappointed at malfunction of the state policy, a scholar-recluse chose to forgo wealth and fame; they wandered in nature (to learn more about the landscape painting practice of scholar-recluse wandering in the wild, please refer to Margaret Hitch’s study), wrote poetry and made friends with like-minded scholars. The Northern Song poet Lin Bu (967–1028) lived a reclusive life in the Solitary Mountain by West Lake. It is said that he planted plum trees and raised cranes. Flowering plum was his wife and the cranes were his children. Many renowned scholars and officials at Lin Bu’s time responded to his poetry and character with admiration and congenial friendship. The circle of scholars in the Song Dynasty wrote poetry and essays to express their esteem to the independent mind that Lin Bu was exemplary of. The imagery of plum blossom therefore implies the character of a man of integrity and culture. In harsh winter when most plants could not survive, the plum tree flowers, emitting subtle fragrance in spite of snow and frost. The qualities of plum blossom are therefore concurrent with that of a scholar of elevated mind. A number of poetry, essays, and paintings from this period were created by intellectuals featuring plum blossom, which served as an emblem of their pursuit.

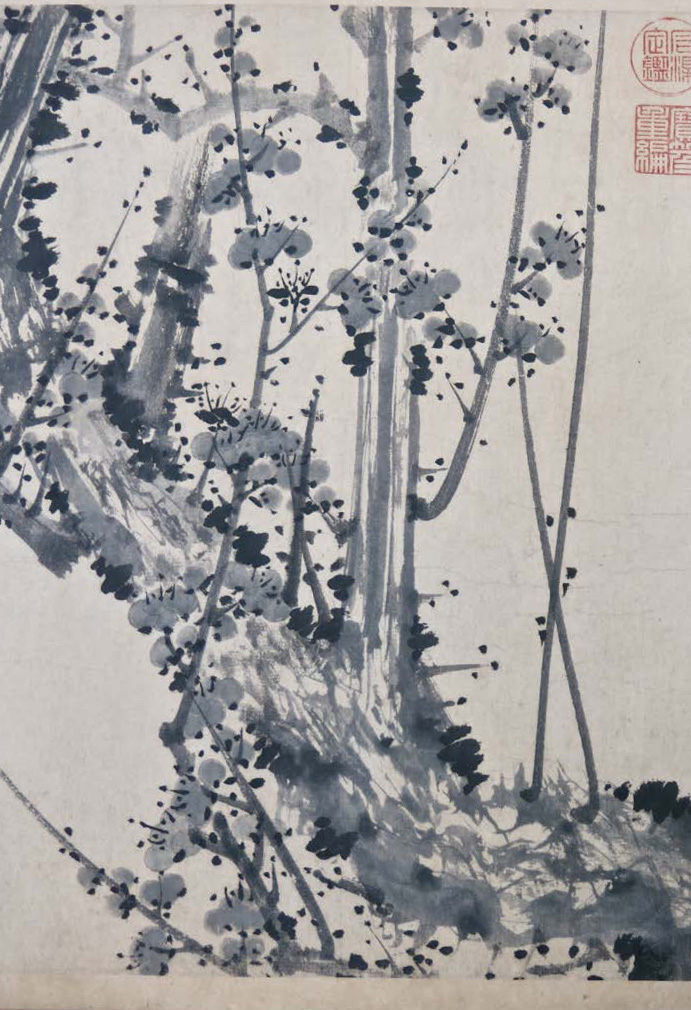

The Ink-plum genre: the scholarly taste

Court paintings treat the plum blossom with refined white pigment and often times portray plum blossom together with birds or other plants. The painters or patrons of the paintings seemed to attach more worth to the physical beauty of the plant. Further, they treat birds, plums, bamboos or other plants not as much in favor of their particular abstract qualities, rather, treating them as a category of elegant things. On the contrary, as for the educated scholars and literati artists, they developed a genre of plum painting–Ink-Plum as an alternative genre to convey their scholarly taste, moral pursuit, and political ideal. The monochrome plum painting aimed at amusing themselves or like-minded friends through evoking emotions and values by ink play or brushwork rather than by naturalistic representation. This distinction in painting styles of the flowering plum was also consistent with the larger social and cultural context: the scholars of the Song Dynasty formed alternative discourse in cultural production and political theory vis–à–vis the court.

Yansou’s handscroll that we are looking into belongs to this scholar’s genre of plum painting. TraditionalChinese writers on art credited the monk painter Zhongern (d. 1123) as the founder of the ink-plum genre. Zhongren was also know by his Buddhist name Huaguang. The ink-plum genre suddenly appeared in his art around 1100.8 A Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) scholarSong Lian (1310–81) discussed Zhongren’s concerns behind inventing the ink-plum genre:

Now the flowering plum bears a lonely and lofty, great and extraordinary moral fortitude. Miring it among common birds and vulgar plants, how can one not call it a hardship! Fortunately, the master Zhongren rose at Huaguang Mountain in Heng (modern Hunan). Aroused, he swept it all away. Dotting on dark ink, he made ink blossoms and he added limbs and branches. They were just like (LinBu’s) ‘scattered shadows horizontal and slanted’ beneath the bright moon. Mo wei laoren (Huang Tingjian, 1045–1105) greatly increased their appreciation. Thus the flowering plum was pulled out of the mortification of muck and mire.9

Therefore when we are viewing Yansou’s ink-plum handscroll, which treats plum blossom as the only pictorial subject and is done in monochrome ink, we need to be conscious of the social and cultural context in the Song Dynasty and the value system of the Song intellectuals.

Other imagery of plum blossom in arts and literature

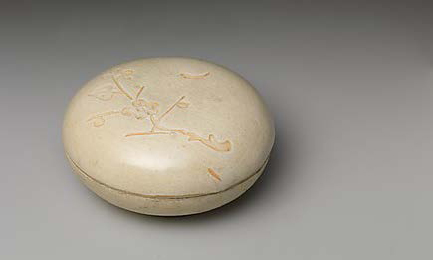

During the Song time, the imagery of flowering plum evolved into an artistic genre common in painting sand everyday objects such as clothing (for example, 7), ceramics (for example, fig. 8, 9), shoes10 and fans (for example, fig. 10). In Sparrows, bamboo, and plum blossoms, the bamboo is a metaphor of a scholar, the plum is a metaphor of a women with literati taste, and the sparrows is a metaphor of rural villagers. That the scholars befriended with farmers is a common theme in the Song Dynasty literature and arts.11 For a detailed discussion on women of literati taste in 13 century Chinese art, please refer to Martin Powers’ China Mirror case study, Women and Arts in the 13th Century.

Fig. 7 – Detail of mirror, Refine Lady with Plum Make-up, bronze, rubbing, diameter: 13.7 cm, Hunan Provincial Museum

Fig. 8 – Covered Box with Flowering Plum, Southern Song (1127–1279)–Yuan (1271–1368)

Dynasty 13th–14th century, Porcelain with cut-glaze decoration, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 9 – Bowl, Song Dynasty, 960–1279

Stoneware, Jizhou ware, Museum of Fine Art, Boston

Fig. 10 – Sparrows, Plum Blossoms, and Bamboo

Unidentified Artist, late 12th century, Fan mounted as an album leaf; ink and color on silk, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

4. Social protocols of viewing

Terms they used to describe the flowering plum

The three colophons attached to Yansou’s handscroll reveal what the scholars in the past were keen about the painting and the plum blossom. Wu Sidao (mid-late 14th century) inscribed the second colophon, which is in a format of ten quatrains, each under a name of encountering plum blossom such as seeking plum blossom, plucking plum blossom, chewing plum blossom, bathing plum blossom, and dreaming plum blossom among others. The third colophon by Jin Shi (mid-late 15th century) was a response to Wu Sidao’s inscription, adopting the same titles, format and rhyme but creating new poetry. Jin Shi inscribed that “The solitary root is covered with ice and frost, I plant it in the old thatched hut of Lin Bu.”12 Wu Sidao said: “plant the solitary root of the plum blossom in the hall and wait for the spring; Lin Bu knows that I am also a like-minded with him…I love to chew the plum blossom just as tasting the snow.”13 Both of them, when mentioning “solitary root”, probably referred to the major trunk depicted in Yansou’s painting. But what does “solitary” mean here? Wu Sidao and Jin Shi associated planting the solitary root with the Song scholar-recluse Lin Bu, and both gestured that their alignment with Lin Bu, who inspired the ‘flowering-plum cult’ in literature and arts of the literati. As Lin Bu was celebrated for leading a reclusive life and embracing free will, ‘solitary’ here denotes the independence of the mind that scholars and literati artists valued in the Song Dynasty. This legacy, evidenced by inscriptions of Wu and Jin, is also evocative for poets of later generations after the Song Dynasty.

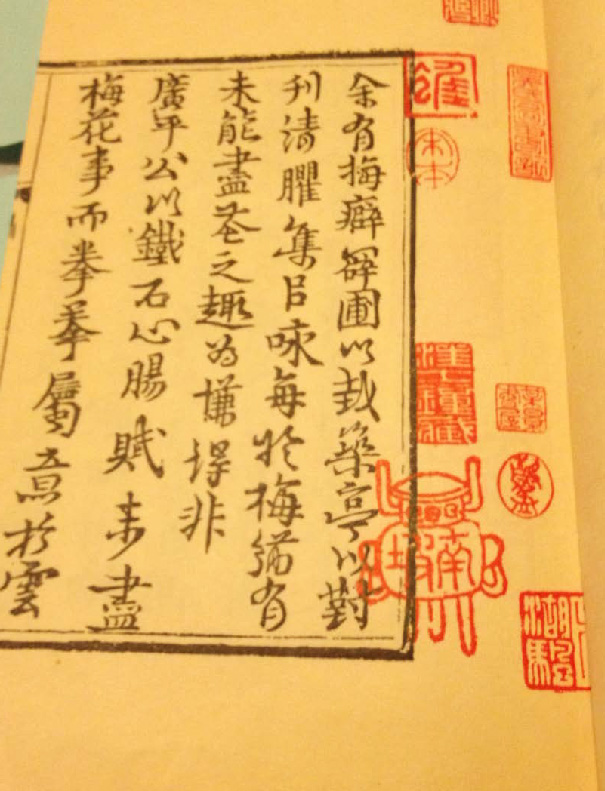

Other than ‘solitary’ (孤, gu), the colophons on Yansou’s painting also indicated that icy (冰, bing) and pure (清, qing) as the ‘bones’ or characters of the plum blossom. This resonated with the literati Su Shi’s verse on plum blossoms: “the flowering plum’s bones are of jade and snow, and their souls of ice”. The word ‘icy’ means calm, objective and impartial character in judgment, and ‘pure’ signifies integrity. Hence these features of the plum blossom were not new perceptions from the inscribers of Yansou’s handscroll, but were what intellectuals in the Song Dynasty admired and aligned themselves with. The Song Dynasty scholar Song Boren (act. c. 1240) created Manual of plum-blossom likenesses. It contains one hundred woodblock images and matching poems devoted to different forms of the flowering plum in its life cycle from bud to bloom and to withering. In his own words, Song Boren created the painting manual not to compete with literati plum painters like Zhongren and Yang Wujiu, but to better appreciate the character of the flowering plum in its full dynamics and enjoy it with his friends.14 In the preface of the manual (fig. 11), Song Boren elucidated the correspondence between flowering plum and scholar-recluse:

(The plum blossom’s) character is cold, pure, unique, elegant and has a sense of classicality, not being tainted at all by the corrupt world. Hence the plum blossom is no different from the two recluses Bo Yi & Shu Qi, the four recluses from the Shang Mountain, the six liberated poets of the bamboo streams, the eight drunk recluses, the nine old scholars from Luoyang, the eighteen scholars from Yingzhou, who led a bohemian life, and were independent from the worldly disturbances.15

These words indicated that to the readers in the Song Dynasty, flowering plum painting or poetry were reminiscent of the scholar recluses of the historical past who embraced independent mind, integrity, and impartiality. More remarkably, Song Boren quoted his friend’s words to inform readers what’s essentially expressed in this painting manual:

Such a book will move the men who reveres the Emperor and harbors deep concerns of the state. These men would like to take the responsibility as a general or a minister to promulgate virtue and rightful policy in the state, ultimately bringing peace to the country. 16

Likewise, to contemporary viewers as well as the inscribers of Yansou’s handscroll, viewing the ink-plum painting recalled to them not only the flowering plum in nature, but also the scholars’ values of integrity, independence and social responsibility. Moreover, the ink-plum also unveils to the inscribers and other viewers the character of the artist–Yansou. As the first colophon comments that “the tip of the brush utters the jade-like character.” “Jade-like character” here describes the pure blossoms, but it also refers to the integrity of the artist.

Re-thinking Yansou’s handscroll in light of word and image inter-relation, one would recognize multiple layers of response displayed here. The colophons are not only response to the plum-blossom image, but also to the artist, to the scholar-recluses in the past, to the actual flowering plum, and among the painting’s inscribers themselves.

Jin Shi’s inscription (left) and Wu Sidao’s inscription (right)

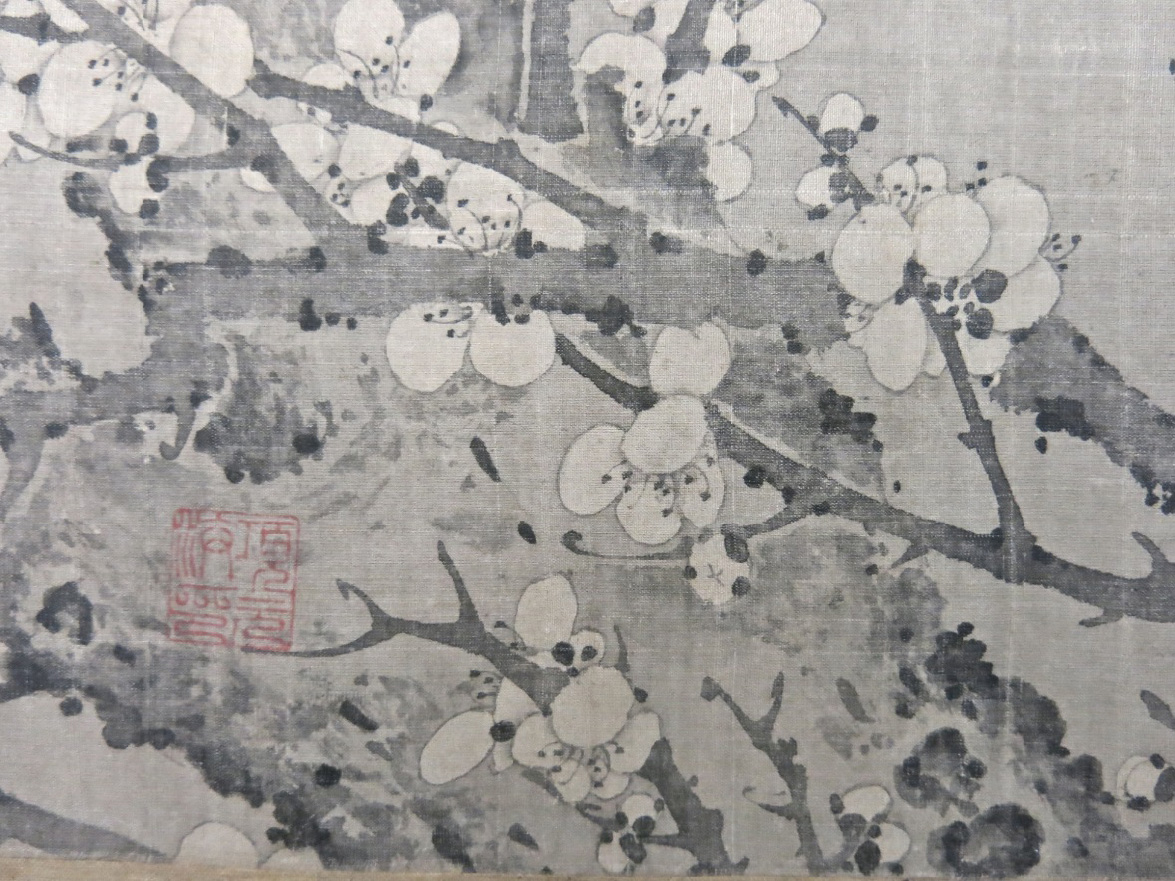

Detail of Yansou’s Ink Plum Blossom

Fig. 11 – Preface, Song, Boren, Manual of plum-blossom likenesses (Song Ke Mei Hua Xi Shen Pu).

Beijing: Wenwu chu ban she, 1981

5. Plum Blossom as a self-portrait: Yansou’s projection into the ink-plum

The technique that Yansou used to paint the ink-plum is termed the reverse saturation technique that appeared by the end of the twelfth century. The ink wash was evenly applied to the silk, leaving reserved areas of the silk to represent the white plum blossoms. This technique was invented especially to create the atmosphere of plum blossom under the moonlight or in the snow. Different from the saturation technique used by Zhongren (whose painting did not survive, but the saturation technique can be traced in Zou Fulei’s painting Breath of Spring17 [fig. 12]) who applied ink wash alone to paint the blossoms without outline, the ink wash background in Yansou’s handscroll highlights on the white and pure properties of the flowering plum. In addition, the contrast of the whitened flower and the darkened ink wash background fabricates environment such as winter after snow or a moonlit night. This makes Yansou’s handscolls more evocative of poetic scenes. Moreover, the heightened whiteness of the plum also accentuates the icy and pure quality of the flowering plum. It is not certain if Yansou’s ink-plum was made after the appearance of Manual of Plum-Blossom Likenesses, however, the forms of the ink-plum blossoms in this handscroll resemble those in the Manual. This was most likely Yansou’s deliberate choice to situate the repertoire of this painting in the larger context of scholarly style in painting plum blossom, since Song Boren belonged to the circle of scholars and literati artists.

The techniques and styles that Yansou chose to paint the ink-plum serve as visual clues of Yansou’s scholarly taste and values. The painting can be perceived as a mirror image, or self-projection of the artist Yansou. This can be evidenced by the first anonymous colophon which points out: “the censorate official in his plain scholar robe resembles the horizontal and slanted plum branch over the waters.”18 As Wu Qiu-ye argued that Yansou was the Southern Song scholar He Menggui,19 who was a censorate official when this painting was made, we can infer from the colophon that the plum blossom was perceived as a projection of Yansou. Both of them had “jade-like” character, or integrity and independent mind.

Similarly, when the Song scholar Xiang Shibi (d. 1261) wrote a postface to Song Boren’s Manual, he commented on Song Boren:

His soul and spirit resonate with that of the plum blossom, therefore he can write poems (on plum blossoms) without techniques, he can paint (plum blossoms) even with no artistic skills…The manual is limited in space but the idea it evokes is infinite.20

Therefore to scholars and literati artists, because their character match that of the plum blossom, as if the flowering plum is just a projection of themselves, they can portray the plum blossoms without intentional effort. The plum blossom itself evokes the image of a high-minded scholar. Thus, because the flowering plum in Yansou’s painting is unified with the scholar, Yansou had no need to portray another scholar appreciating the plum blossom, as what the court painter Ma Yuan (active ca. 1190–1225) created in Viewing Plum Blossoms by Moonlight (fig. 15). The meanings of the Yansou’s Ink-Plum are much more condensed and so would come to the like-minded scholars naturally while viewing the painting.

Fig.12 – Detail of Zou Fulei, A Breath of Spring,1360, (active mid-14th century), Ink on paper, 34.1 cm x 223.1 cm, Freer Gallery of Art

Detail of Yansou’s Ink Plum Blossom

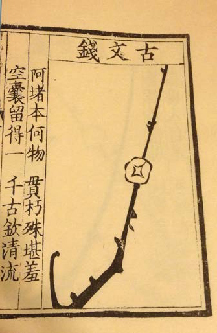

Fig. 13 – Page from the reproduction of Song, Boren, Manual of plum-blossom likenesses (Song Ke Mei Hua Xi Shen Pu).

Beijing: Wenwu chu ban she, 1981.

Fig. 14 – Page from the reproduction of Song Boren,

Manual of plum-blossom likenesses (Song Ke Mei Hua Xi Shen Pu).

Beijing: Wenwu chu ban she, 1981.

Fig.15 – Ma Yuan, Viewing Plum Blossoms by Moonlight, early 13th century, fan mounted as an album leaf, ink and color on silk

8. Bickford, Maggie. Bones of Jade, Soulof Ice: the Flowering Plum In Chinese Art.New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1985. P.60↩

9. Translation of Song Lian’s “Inscribing an Ink Plum by Xu Yuanfu” is cited from Bickford, Maggie. Bones of Jade, Soul of Ice: the Flowering Plum In Chinese Art. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1985. P.28↩

10. Bickford,Maggie, Ink Plum: the Making of a Chinese Scholar-painting Genre.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. P.34-39↩

11. For a detailed discussion of this artistic theme of the scholars and rural villagers, see Cheng, Wen-Chien “Drunken Village Elder or Scholar-Recluse? The Ox-Rider and Its Meanings in Song Paintings of ‘Returning Home Drunk’” in Artibus Asiae, Vol.65, No.2 (2005), pp.309-357↩

12. colophon by Jin Shi: 孤根入手帶冰霜,移向林逋舊草堂↩

13. colophon by Wu Sidao: 移得孤根候旾色,林逋知我也非常↩

14. 今非其譜也,余欲與好梅之士共之……茲非為墨梅設,墨梅自有花光仁老、楊補之家法,非余所能。Song, Boren, Manual of plum-blossom likenesses (Song Ke Mei Hua Xi Shen Pu). Beijing: Wenwu chu ban she, 1981.↩

15. Song, Boren, Manual of plum-blossom likenesses (Song Ke Mei Hua Xi Shen Pu). Beijing: Wenwu chu ban she, 1981.↩

16 此書之作,豈不能動愛君憂國之士,出欲將,入欲相,垂紳正笏,措天下於泰山之安。Song, Boren, Manual of plum-blossom likenesses (Song Ke Mei Hua Xi Shen Pu). Beijing: Wenwu chu ban she, 1981.↩

17. That Zou Fulei’s Breath of Spring adopted Zhongren’s painting style of the plum was discussed in a colophon of this painting. The English translation of the colophon can be found in Sirén, Osvald. Chinese Painting: Leading Masters And Principles. London: Lund Humphries, 1956, P.161↩

18. 霜臺御史繡衣人,藏得橫斜水面真↩

19. Wu, Qiu-ye, “Exploring the author of Ink Plum Blossoms” in Journal of the study of Calligraphy and Painting (shuhua yishu xuekan), Vol.13, P.157-172↩

20. Xiang Shibi, Postface in Song, Boren, Manual of plum-blossom likenesses (Song Ke Mei Hua Xi Shen Pu). Beijing: Wenwu chu ban she, 1981.↩