In China today, a new round of international competition and integration of global cultures is playing itself out in many walks of life. Although eighteenth-century European gardens were almost exclusively for the aristocracy and Chinese gardens were mainly for the affluent acted as the sites for cultural competition, today the mass media and globalized popular culture have made cultural competition an integral part of our everyday lives.INTERNATIONAL SPORTS COMPETITION AND NATIONAL IDENTITY

Today, in place of gardens, sport is the game of choice for China and many countries for promoting national identity in the cultural arena. When China decides to reach out to the broader world, international sport competition can be a starting place for serious changes in international relationships. In the 1970s, Chinese leaders opened diplomatic talks with the United States through the so called “Ping-pong diplomacy” (as featured in the film Forest Gump), and an invitation to the American table tennis team to visit China broke the ice for the normalization of relations between the two nations.

|

|

American Ping-pong players made the first visit to China in 1971, which broke the ice for the diplomatic relationship between the two nations.

Source: www.xinhua.net.

THE OLYMPICS

When the Chinese delegation made its triumphant appearance in the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984, the entire nation saw it as a symbol of China’s reemergence from the ruins of political anarchy toward its acceptance as a member of a broader international community.

|

|

Chinese women’s volleyball team winning the gold medal at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics

Source: http://gb.chinabroadcast.cn/mmsource/images/2004/04/12/sc040412028.jpg.

China has since become a major player in the games and is preparing for the 2008 Olympics Games, which will be held in Beijing. This helps us to see how tools developed in one region can be readily adopted and benefit peoples of another region. The “natural” garden was originally developed in China, but in the eighteenth century became the cornerstone of England’s claim to cultural achievement. Likewise, the Olympic games can be traced back to ancient Greece, yet, in the twenty-first century, is serving China’s interests.

Because of increasing trends in globalization, sports not only can symbolize national competition but also can represent the integration of cultures. For example, today it is common to find foreign players in Chinese soccer clubs, and many American fans love watching Yao Ming’s athletic prowess in the NBA games. The movement of players and the creation of new cultural identities in sports and in the cultural arena manifest a broader role that China has fulfilled throughout history in the changing contemporary world at large.

MATERIAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CULTURAL COMPETITION

How does cultural competition, as seen in sports, manifest itself in material form in contemporary China? One way is through the construction of monumental architecture. If gardens were meant to impress foreign visitors in the eighteenth century, then monumental architecture would fill a similar function today, albeit for a different audience. Today, China claims three of the ten tallest skyscrapers in the world.

|

|

Jinmao Tower in Shanghai.

Source: http://www.smartshanghai.com/venue/1956/Jinmao_Tower.

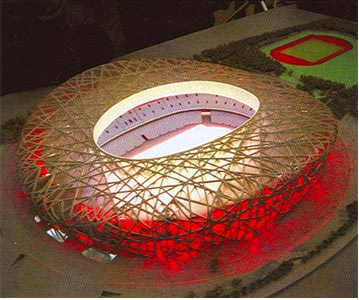

In addition to the sheer height of the sky scrapers, style is also important. In its construction boom, China has entered the competition to become the testing ground for provocative and novel modern architecture designed by leading architects around the world, such as its water drop–shaped National Theater Hall on the Tiananmen Square and the bird-nest shaped Olympic Stadium.

|

|

Chinese National Theater Hall in construction.

Source: http://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Grandthe.gif.

|

|

The construction of a modern looking Chinese National Theater Hall (upper right) near the Forbidden City sparked heated debate on the preservation of Beijing’s historical landscape. Photo courtesy of Li Min.

|

|

Model for the Birdnest-shaped Beijing Olympic Stadium.

Source: http://www.cdb.com.cn/WebSite/cdb/UpFile/File980.jpg.

The open acceptance of radical architectural designs resulted in a confrontation with the traditional cityscape and historical landmarks, and remains a subject of heated debate in contemporary China. Likewise, in the United States, Chinese-born architect I.M. Pei was chosen to design the east building of the nation’s National Gallery of Art. And, as in China, monuments can be controversial. When Asian-American architect and sculptor Maya Ying Lin designed the Vietnam War Memorial, many Americans objected to the absence of traditional, allegorical, figurative groups. Even so, this monument today draws more visitors than either the Washington Monument or the Lincoln Memorial.

PUBLIC SPHERE

Besides sports and architecture, which both rely on heavy state sponsorship, what is occurring in the public arena in terms of culture and international relations? For almost a thousand years prior to the founding of the People’s Republic, artists in China were able to work freely and sell their art in an open, competitive market. There were art critics, art dealers, art appraisers, and art galleries in China as early as the tenth century, and over time the passion for art collecting only diversified and increased. This led to much experimentation in both style and technique, so that we find artists in China painting with dish towels, sugarcane stalks, bare fingers, or just throwing paint hundreds of years before European artists would venture such techniques. After 1949, the Chinese government—following the Soviet model—managed art production in China in state-run institutions, such as art schools or film studios. This applied to all media, including film, drama, music, and professional painting. The Chinese state also sponsored international tours specifically aimed at promoting international relations and cultural exchange, as do nations further west, including the United States. In recent years, the government has gradually pulled out of these cultural arenas, and state-sponsored international cultural exchange has been replaced by the internationalization of art production and the open art market. A Chinese film can be jointly produced by a multinational crew and distributed internationally, or a painter may work in her studio in Hangzhou and be represented by studios in New York. Once primarily sponsored by the Western diplomat community in Beijing, the exhibition of modern art now has major venues catering to an emerging art market responsive to independent art criticism. Relieved from the burden of promoting “socialist values,” artists in China once again experiment actively with diverse ideas and styles, while making keen observations of market trends.

|

|

Slogans from the Cultural Revolution Era was intentionally preserved at Factory 798, once a military manufacture designed in the Bauhaus style by a German architect, later turned into a major venue for a thriving Beijing art community. Photo courtesy of Li Min.

While no longer the sole sponsor of art production, the Chinese government—like other modern governments—takes seriously its role in providing stewardship for the nation’s cultural heritage. It has invested millions of dollars for purchasing back Chinese art treasures from the international market. For example, a museum financed by an arms sale corporation for the Chinese army purchased the bronze animal heads looted from the Garden of Perfect Enlightenment by the French and British troops. This effort to reclaim the cultural legacy damaged by colonialism reveals the continuing importance of culture in international relations.

|

An armed police on guard next to the bronze monkey head at the Poly Museum in Beijing. The bronze statue was looted from the Garden of Perfect Enlightenment by the French and British troops in the nineteenth century.

Source: http://www.newgx.com.cn/newspic/uploadpic/200510/

f13b07d90207476f920f45c1d4d18929.jpg.

EXPANSION OF PUBLIC SPACE, GLOBALIZATION, AND TECHNOLOGY

The final and most important front of culture and international relations is the expansion of public space and the globalization of culture created by digital technology. A thousand years ago, printing was invented in China, which created the first “public space” for political debate through the use of printed books, prefaces, personal notes, and essays. Half a millenium later, when print technology arrived in Europe, printing similarly opened up a space for public debate. In recent years, a similar revolution has occurred following the invention of the internet in the United States. Access to the internet dramatically expands the traditional public space for political expression in all countries. In China, although state censorship still exists, it is much more relaxed on the internet than in print media. As a result, the internet has played a critical role in the liberalization of people’s political views and in providing access to diverse opinions on world events. However, technology can be a double-edged sword. Copyright infringement as a result of pirating and downloading of entertainment programs is a problem in all countries, including the United States. However, the topic has often emerged as a source of tension in China’s international relations, particularly with the United States. On the other hand, the easing of government control in cultural production and art market has once again allowed civil society to grow and flourish in China.

Children from a rural village of northern China displaying

the “peace” sign found in Western images.

Photo courtesy of Li Xu. |

|