| People in ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, China, and many other parts of the world invented rituals, prayers, and other activities in order to divine the future. These divination activities often produced texts. As a group these texts may be regarded as belonging to the same genre, the genre of divination texts.

Divination texts come in many varieties but share a few common features:

- They all seek to divine the future.

- They often assume an “if. . . then” format: “If you do X, then Y will occur as a result.” In this sense, they have a quasi-logical, proto-scientific character to them. They are attempts to systematize the acquisition of knowledge about the future, and so.

- They tend to be formulaic rather than prosodic.

- The text often is mediated through a specialist of some sort: an oracle, a shaman, a priest, or some other divinatory expert.

- There is usually some level of spiritual agency involved whether explicit or implied. Consequently the “author” of texts in this genre is rarely an ordinary writer. In some cases these texts were regarded as the direct proclamations of gods or spirits. In other cases they were treated as the advice of men or women considered expert in predicting the future.

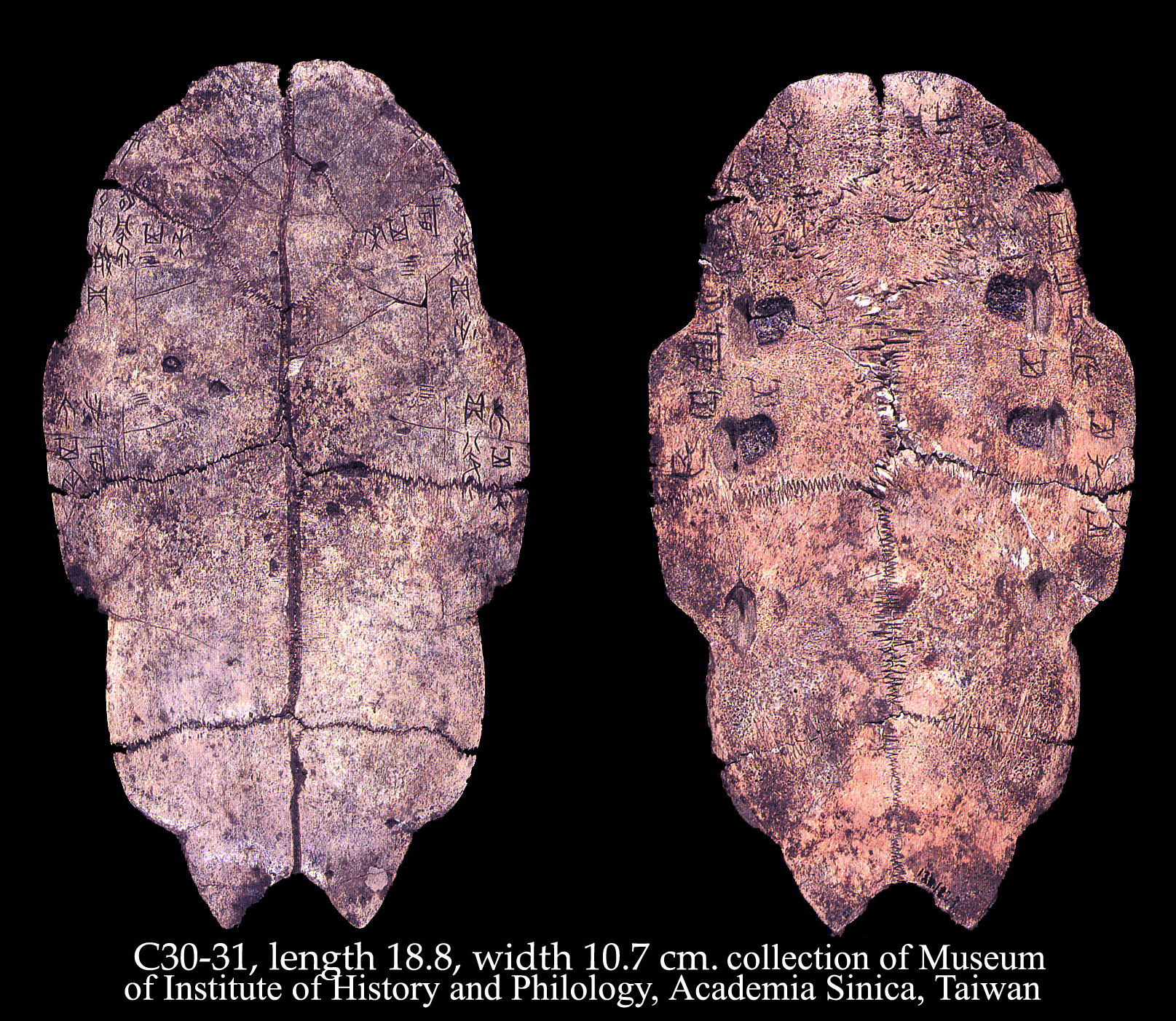

There is a long tradition of written divination texts in China. More than three thousand years ago, the Shang people (1700-1027 BCE) had already developed an extensive method of divination by oracle bones, which form another genre of divination “texts” (for more information see the unit on early writing in China).

The existence of Shang oracle bone inscriptions indicates that even at that time people already believed that certain events on particular dates in the future were pre-determined, and that these events could be made known through specialist methods.

The Yijing, 易經 or Book of Changes is another divination text, one that is still in use today. Some believe that Confucius studied and edited it. The Book of Changes contains explanations of the meanings of the Hexagrams, a collection of sixty-four abstract line arrangements, which are used in conjunction with various methods of casting milfoil.

Although the Hexagrams are not built on a calendrical system, the Book of Changes nevertheless reveals a set of underlying assumptions that are similar to those of the Daybook. First, both texts assume that human affairs can be categorized into a limited number of phenomenal types, such as Yin and Yang, lucky or unlucky, “earth” and “water” elements and so on. Secondly, both texts provide formulaic explanations or predictions. Finally, both texts organize their predictions within a cyclical structure of reckoning.

Now that you have some information about the Daybook,

learn how to read its different parts: HOW TO READ IT

|