WHAT IS THIS THING?

CASE 3

Culture and International Relations in the 18th Century

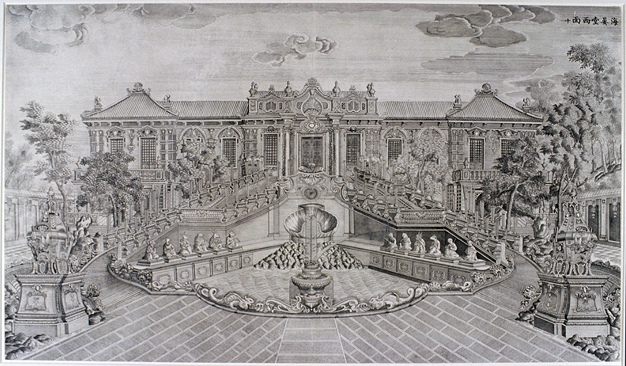

Hall of the Calm Seas.

Hall of the Calm Seas.

Series of 18th-century engravings by Li Yantai of the Yuanmingyuan Palace.

Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

You are looking at an image of a rare engraving of the Hall of the Calm Seas, which is one of the European-style pavilions designed by Europeans in China for the Garden of Perfect Enlightenment. Emperor Qianlong had the artisans in his palace workshop make a set of twenty prints to commemorate some of the scenes that visitors would find in the garden. Two hundred sets were completed in 1786, but only five sets are extant today. This particular print is from the set preserved in the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, California. Prints like these belong to a class of objects that some people call “transcultural,” that is, they cannot be understood entirely within the cultural framework of one nation, but have to be understood as products of a dialogue between two or more nations. Such objects are typical of the modern world.

ENGRAVINGS

An engraving is a type of printed image in black ink on white paper. An artist may first draw the image and provide this to an artisan called an “engraver,” who copies the image onto some carvable material, such as wood, stone, and linoleum, or onto a metal plate. European engravers preferred the technique of working on metal plates and had developed the art to a high level of sophistication. For example, European engravers would be careful to copy the image in reverse so that when printed it would appear like the original. Using a pointed engraving tool called a “burin,” engravers would carefully follow the lines of the original while cutting grooves into the metal plate. When finished, these grooves would hold the ink that the printer, who might be another artisan, would coat onto the metal plate. The printer then would use special ink to cover the plate. When the plate was wiped with a cloth, the ink would remain in the grooves but not on the surface. The deeper and wider the groove, the bolder the line would appear in the print. By engraving many small lines, an engraver could create shadows and tones. This particular engraving is a copperplate engraving. Since copper is a relatively soft metal, it very suitable for this engraving process.

After being inked, the plate would be placed face downward on the paper, and a press machine would be used to apply pressure evenly so that the ink in the grooves could make contact with the paper. After a short time, the plate and paper would be removed from the press and carefully separated. A single copperplate could make many impressions before the metal grooves began to wear down. Then the lines could be cut deeper. or an entirely new plate could be engraved. Sometimes the artist would sign the prints to increase their value on the art market and the printer also might place a mark somewhere to record his role. Sometimes the paper contained a watermark to indicate the manufacturer. The metal plates could be stored away for later use, or destroyed so that no other copy could be made.

METAL ENGRAVING

Metal engraving was an art known in many cultures since early times, including in China. However, metal engraving was mostly used to decorate the surfaces of objects. In China, engraving with woodblocks to print images and texts was found to be faster, more economical, and perhaps more pleasing. Woodblock engraving was done by carving away the wood from the lines so that they stood out, which is called carving in “relief,” whereas copperplate engraving is called “intaglio,” which means “cutting into.” In fact, the earliest woodblock print in the world that can be dated was produced in China, which is an image and text of Buddha from 868 AD. By the sixteenth century, Chinese artists and engravers had developed the art of polychrome woodblock printing to a high level of perfection so that a printed sheet could convincingly imitate the many fine effects of brush and ink, which included subtle shading effects. Artists and engravers in Japan also developed this art, serving what may have been the largest mass market for engraved pictures in the world at that time. Metal engraving for printing developed in Europe in the fifteenth century, probably in Germany or in The Netherlands.

It soon became popular in neighboring countries, especially in Italy and France. Compared to woodblock engraving, metal engraving was more laborious and expensive and could show more detail, factors that might have appealed to the largely aristocratic audience for European engravings at that time. Metal plates also were more durable than wood and thus theoretically could print more images.

Looking at the technology of printing, we find that printing, although it was invented in China, soon spread across Eurasia and took on distinct forms in different places. Whatever form it took, engravings made it possible for educated people at either end of Eurasia to learn about the tastes and habits of peoples at the opposite end of the continent. This made possible the phenomenon of international cultural competition that appears very clearly in the designs of eighteenth-century gardens.