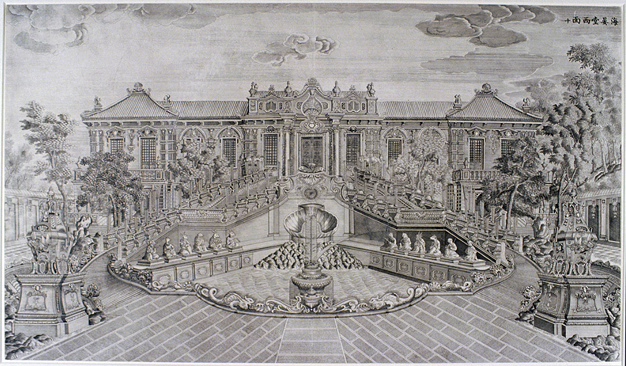

Hall of the Calm Seas

CASE 3

Culture and International Relations in the 18th Century

How to Read It: HALL OF THE CALM SEAS

Hall of the Calm Seas.

Series of 18th-century engravings by Li Yantai

of the Yuanmingyuan Palace.

Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

The Hall of the Calm Seas was the largest and tallest of the European Pavilions and was completed circa 1759. The pavilion had two stories and very grand, circular staircases on both sides that led from the ground level to the ornate, central door on the second level. The emperors were surprised to learn that people in Europe lived in multilevel buildings. Early modern paintings in China do show that multilevel restaurants existed, but, when it came to personal habitats, people in China commonly lived in mainly one-story buildings.

At the end of the sixteenth century, educated Europeans began to arrive in China. Most were Jesuit priests and had been sent to disseminate the Christian religion. The Qing emperors employed a small group in the palace who were experts in astronomy, mathematics, painting, glass-making, architecture, music, and other skills. Several Jesuit priests collaborated to design the European Pavilions with Guiseppe Castiglione (1688–1766 AD), an Italian Jesuit priest who served as the main architect. He chose to use the Baroque style that was popular in Europe at the time. The Baroque style displayed elements of Greek and Roman architecture, but was more complex and dramatic because it used more elaborate decoration. Castiglione’s buildings are mostly based on palaces in Italy, with influences from France and other countries.

Above the doorway are large stone vases and other European-style decorations on the roof that are common baroque features. However, the shape of the roof defers to Chinese taste with its curved eaves and use of tiles. Look more closely and you may be able to identify some carved fish at the end of the roof eaves and even heads of auspicious birds on the roof above the central door. These and various other animal decorations were common features in Chinese temple and palace architecture and expressed a hope that the building will escape any harm or evil (not unlike Christian practice of blessing buildings or just about anything else at that time as protection against evil). Although the print is in black-and-white, the European Pavilions were in fact very colorful. The roof tiles were in brilliant colors, such as blue-green, red, and yellow. Yellow was the imperial color, blue could represent the sky, and red was considered to be very lucky. The walls of the buildings were painted in softer pastel shades. The windows and edges of the buildings used stone and marble, as well as wrought-iron. The windows were very large and often contained panes of glass. This use of glass was relatively common in Europe by this time, but its usage in China was still rare. Most Chinese windows were covered with oiled paper for protection against the cold, although some used silk to let in the air during hot weather. After the Jesuits arrived, they established a small glass factory at the emperor’s request. In front of the building on the second floor, you can see balconies on both sides. The stairs led to a terrace in front of the entrance. When the emperor sat in a throne on the terrace in front of the main door, he could overlook the intricate fountains below and look beyond at other parts of the Garden of Perfect Enlightenment. In all these ways, the Hall of Calm Seas offers an example of transcultural processes of artistic creation.