NOW AND THEN

CASE 1: Women and Arts in the 13th Century

FASHION AND ACCESSORIES IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA

Before you even speak to someone, you may have already intuit some information about this person simply from his or her clothing. Depending on what someone wears, you might be able to guess something about the person’s profession, taste, personality, or class. Fashion is a soundless language and an identity marker, which communicates much about how you want to represent yourself. In fact, even if someone deliberately avoids fashion, this, too, becomes a statement in its own right.

Clothes and accessories constantly change with time, reflecting the transformation of society, ideology, economy, culture, aesthetics, and consumption. In China during the Song Dynasty, a painted fan or a bronze mirror could be part of a woman’s or a man’s personal accessories. Because Chinese back sides of mirrors (like fan paintings) could display pictures and texts, the mirror was a powerful medium for making statements about one’s personal values and ideals. Personal accessories used today have a similar function, but today we can choose from a wide variety, including handbags, watches, scarves, perfumes, and so on. The fact that women in Song China could buy a mirror with an inscription challenging traditional feminine roles indicates a changing social condition tolerant of greater openness at that time. The availability of such a mirror in the Song fashion market, as well as the presence of a consumer group to make its production financially feasible, suggest that these new social values were shared by a sizable group of educated women consumers. From literary sources, we know that even village girls were attentive to fashion since the Song Dynasty, and painted fans could be purchased to fit almost anyone’s pocket book.

A silver cosmetic box from a Southern Song tomb in Fuzhou.

Photo courtesy of Li Min.

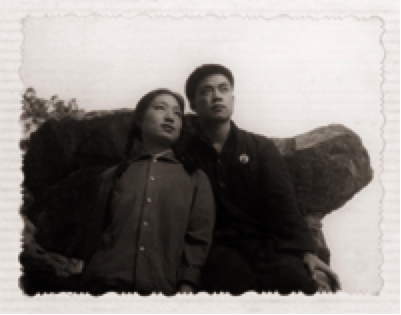

Now let us turn to women’s fashion and its interaction with social transformation in China today, which has been assuming an evermore global character. This change can be appreciated by a sharp contrast with that of fashion three decades ago. In the 1960s and 1970s, the government advocated equality between women and men: therefore, women were encouraged to join the work force as genderless, proletarian workers. Black, gray, navy blue, and army green dominated women’s fashion and military uniforms, and cotton work clothes was the dominant material for both men and women. People received their fashion cues from mass political campaigns mobilized by the Chinese Communist Party and obtained the textiles from state-run stores with rations tickets. Femininity and individuality were regarded as signs of “bourgeois ideology.”

A couple in typical dress code of the late 1960s.

Source: http://image2.sina.com.cn/lx/2003-04-01/3_8-1-915-101_20030401103121.jpg

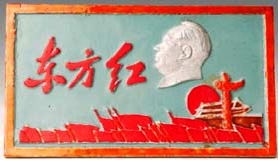

Political ideology dominated everyday life, of which fashion accessories were no exception. Children wore a red scarf to mark their membership in the League of Young Pioneers; young people proudly wore a military uniform and a belt as the ultimate fashion statement; and ordinary folks wore a pair of sleeve cover over their elbows to protect the scarce fabric and to give themselves a proletarian “look.” The only accessory in no short supply was the badge bearing Chairman Mao’s portrait, which was pinned on one’s shirt to show loyalty to the great leader. Factory workers used their own manufacturing technique to design and produce these badges, which came in every imaginable material and form. They were objects of competition and envy as people obtained them through gifting, exchange, and distribution. Today, these accessories have become a collector’s items (http://museums.cnd.org/CR/old/maobadge).

Metal badges bearing Chairman Mao Zedong’s portrait.

Due to reform policies, the fashion world in China changed during the 1980s and has accelerated to become a booming industry today. In the 1980s, women abandoned their military-style uniforms and worker’s overalls, and the color and style of women’s fashion became more feminine. Popularized by films and television programs, waves of fashion style swept through China following trends in Hong Kong and Taiwan. If yellow skirts were the rage, you would see everybody wearing one on the street until the next fad arrived. Rural industries in coastal Zhejiang Province supplied the fashion market with cheap hairpins, scarves, shoes, handbags, and other accessories with unlimited diversity.

As the free-market economic reforms provided more wealth to Chinese society, the gap between those with a high income and those with a low income widened, especially between those working for the multinational corporations and those laid off from the once glorious state-run enterprises. Inevitably, the proletarian ethos fell out of fashion. The appearance of a large group of highly educated white-collar women reshaped the work force and women’s social ideals. They presented themselves, not as a genderless counterpart to male workers as in the revolutionary years, but as intelligent and successful women in their own right. To them, a beautiful appearance and personal achievement do not necessarily contradict each other; rather, they presented themselves as a perfect combination of both (an ideal also found on some Song Dynasty fan paintings). They preferred elegant professional clothes and tasteful cosmetics, and gradually became the major patron group of the fashion market. Both international and domestic brands opened shop in major cities catering to the reawakened consumer society in China.

Mass media of course is very important in promoting beauty and fashion in today’s China. Television programs and fashion magazines emerged during 1990s, serving as a carrier in spreading the latest trends and styles in beauty, fashion, cosmetics, health, fitness, sex, and food. The leading fashion magazines are copublished with international magazines in Europe, United States, and Japan, such as Vogue, Elle, Marie Claire, and Cosmopolitan. Print media, television, and Internet collectively promote the image of middle-class consumers in a cosmopolitan society, meanwhile rearing this market to the benefit of international conglomerates in the fashion business. Accessories and fashion peripherals (cosmetics, fitness, spa, beauty salon, and plastic surgery) flourished.

Teen fashion magazines in China.

Source: http://women.sohu.com/s2005/Oct.shtml

Another striking trend in women’s fashion today is the increasing diversity and the return of traditional Chinese styles in fashion, visible in embroidered patterns, traditional collars, the use of brightly colored silk and so on. As a result, a woman today can choose from a broad spectrum of fashion choices without being constrained by what is in vogue. Retro styles harking back to the 1930s have come back, and a Chinese bride now often wears traditional Chinese dress (red) and a Euroamerican style gown (white) at different times of day for her wedding day. Things have come a long way from the worker’s uniform in the 1970s and successive waves of fashion fad in the 1980s.

A Chinese bride in traditional style costume at a wedding banquet.

Photo courtesy of Li Min

The flourishing wedding photo industry in the last decade

caters to people’s diverse taste.

Source: http://eladies.sina.com.cn/2003-04-01/66973.html

Today, China has also become a major exporter in the world fashion business. International corporations take advantage of the inexpensive labor for manufacturing garments. Many rural workshops have become large labor-intensive manufacturing centers that closely watch the latest fashion trends from Milan, Paris, or Tokyo. China’s own fashion design industry has just begun to take shape. Meanwhile, China remains an active importer of foreign perfumes and cosmetics in department stores, not unlike what you might have seen in a marketplace during the Song Dynasty when aromatics were imported from Arabia through the Maritime Silk Road.