The Chinese Magistrate

CASE 7: Homicide and the Law in 18th Century China

Back to Introduction

In eighteenth-century China there were approximately fifteen hundred administrative districts; the average population of a district in 1800 was about two hundred thousand. Imagine that you have been appointed to administer one of these districts. Your responsibilities include the fiscal, social welfare, security, educational, and judicial affairs of your district. Formally, you occupy the base of a bureaucratic pyramid that reaches up to the emperor in Beijing. Informally you are known as the “parent official” (fumu guan) because you are the official closest to the people. As your title suggests, ideally you will look after the people in your district much as a parent looks after a child.

Your primary qualification for government service was passing the national civil service examination. Your curriculum of study for the exam included philosophy, ethics, and literature. Your short but well-rounded humanities education has instilled in you the shared moral values of the educated elite, but it has provided little in the way of practical administrative skills. Typically, you would bring with you to your new position a staff of skilled specialists, such as a legal secretary, whom you would personally hire and pay. The government office you occupy also has a staff of clerks, constables, factotums, and servants responsible for the routine tasks of governing. What makes your job particularly challenging is that your term of office is three years at most and, thanks to the “rule of avoidance,” you are not allowed to serve in your home area. Term limits and the rule of avoidance are meant to guarantee that you will be an outsider and, therefore, impartial in the jurisdiction you serve. Term limits is also a precondition for promotion, demotion, or dismissal, depending upon the magistrate’s performance.

Of all the tasks you will face perhaps none will be more burdensome than the administration of criminal justice, and the most difficult crime to adjudicate will be homicide, a capital crime. Under the Qing criminal justice system, you are responsible for the investigation, arrest, trial, conviction and preliminary sentencing for all capital crimes. Strict time limits are imposed on each step of the process. As a busy official you will probably rely on your legal secretary to put together case records. But you alone are responsible for the accuracy of the report and concern for your professional future will dictate that you diligently oversee every aspect of the investigation. This is especially true for capital cases because under eighteenth-century Chinese law, all capital crimes are automatically subjected to judicial review at each ascending level of administration, up to and including the emperor. From the standpoint of the county magistrate, the document that receives the greatest scrutiny is a capital case report. Your report, which bears your signature, exposes your professional performance of an extremely complicated and serious task to the scrutiny of all your superiors, including the emperor.

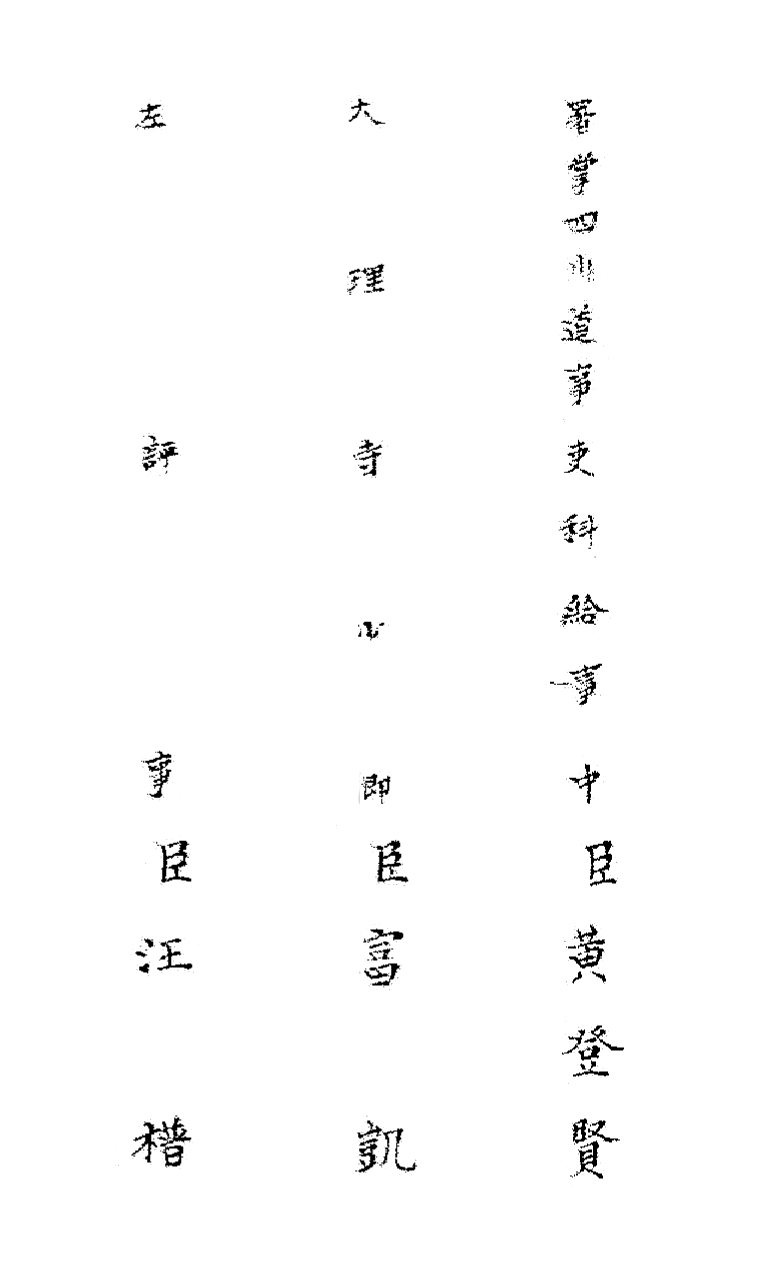

Signatures of the officials responsible for the murder case record of Wen Shaolong

Now imagine you have received a request to investigate the mysterious disappearance of a husband, wife and son that occurred a few years earlier. The brother of the husband has accused several individuals of conspiring to kill his brother and make off with his wife and son. Violent crime is not rare in eighteenth-century China, but, as you will soon discover, this crime is exceptionally complicated and particularly atrocious. Your investigation will reveal that Ms. Zhou, the wife of the murdered man, her lover Yuan Ren, and several other accomplices were responsible for the brutal killing of the plaintiff’s brother. Most shocking, given the prevailing notion of feminine virtue, Ms. Zhou was an active instigator and willing participant in the murder of her husband.